Crossing out the First Amendment?

Published 10:27 am Saturday, March 28, 2015

FRANKLIN

When Teri Zurfluh approached the podium at a recent Franklin City Public School Board meeting to talk about the importance of the system’s gifted program, she almost wasn’t allowed to speak. Members of the audience, many of whom had gathered for the Citizens’ Time section, said she turned red as the board chair interrupted her.

Indeed, Zurfluh hesitated before speaking again, perhaps considering storming out or trying to calm herself, before approaching the podium again. At first her speech was flustered as she self-censored herself to not name specific people other than her children in the system, or even to refer to specific people in a way that could identify them.

Zurfluh, who is the trainer and coordinator with Paul D. Camp Community College’s Workforce Development Center, wanted to tell the school board how good a job the two gifted teachers had done in the system, and to criticize the superintendent for cutting one of the positions when long-time gifted instructor Patti Rabil retired. She also wanted to find out how that decision was made without consulting the division, including principals to her understanding.

She was able to deliver part of her message, lauding the gifted program itself. However, the superintendent has yet to answer questions about how the decision was made.

It wasn’t the only time in the meeting that someone’s words were censored in Citizens’ Time, and it wasn’t the first time board chair Edna King had asked someone to refrain from speaking.

Rewind back to November 2013, when the school board was soon set to make a decision on whether it would renew then-superintendent Dr. Michelle Belle’s contract.

David Benton, a former school board member, was one of many who wanted to talk about what had happened under Belle’s watch. As he started to go into his speech, he was interrupted because he had inferred her title.

“I ask you to not present this,” King told him.

“I have struck all of the places where I used this person’s name,” he responded. “I will not use names.”

“You may not use position as well,” King said. “You cannot present this in open session.”

King invited him to speak in closed session, where only council would hear his words, or to submit it in writing, but she invoked her right as chair to ask him to stop speaking.

Benton didn’t believe that something as important as a decision on a superintendent had to be relegated to closed session, but he did not push the issue any further and took a seat. Ultimately, in December, the board did renew her contract with stipulations, only to back out on that a month later when they ruled she did not meet one of those conditions.

Zurfluh said actions like this are not good for the public.

“It can be a really chilling effect for members of the community, especially parents,” she said. “It takes a lot of courage to stand up in front of that group, and to be shut down is really chilling.”

By chilling speech, Zurfluh means that the rules she called ‘archaic’ are stopping people from addressing the board.

“I had some parents who told me, ‘I’m glad it was you up there. I would never get up there again,’” she said. “That’s the thing that is more frightening, that a policy like this that doesn’t allow people to share is not only chilling speech, but then we don’t get any better. That’s because the school board isn’t going to hear the voices of the people. You have to give the people better than lip service that you value their opinion.”

The specific rule in question is No. 5 of 10: The School Board will not permit speakers to discuss specific personnel or student concerns during the public session, but may be invited to do so during “Closed Meeting.” Names, titles or positions which can identify specific individuals will not be allowed during the public session. Speakers having specific personnel or student concerns may sign-up to speak on these topics during “Closed Meeting.” Only the speaker or representative of a group may be present during “Closed Meeting.” Permission to speak before the School Board in “Closed Meeting” is at the discretion of the Franklin City School Board.

Item No. 8 has also come into question: Persons who address the School Board at Citizens’ Time must restrict their remarks to school matters, must address their remarks to members of the School Board, may not use profanity or vulgar language and may not engage in personal attacks against employees of the school system or other persons.

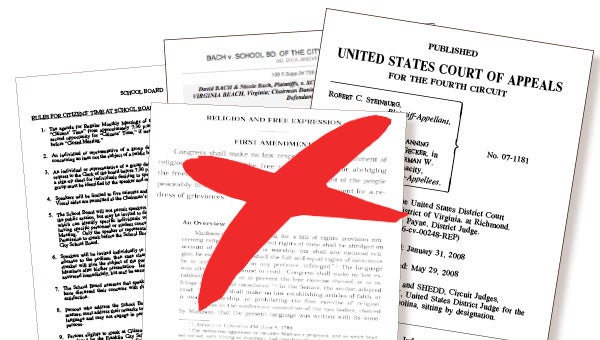

Following January’s school board meeting, The Tidewater News Publisher, Tony Clark, and this reporter were interested in looking into these rules. Several cases were found that questioned policies like Franklin’s, including a local one; Bach vs. the School Board of the City of Virginia Beach. The U.S. District Court of Norfolk found that a policy that chilled protected speech could not stand and was unconstitutional, as a prior restraint upon speech in a limited public forum.

Bylaw 1-48(B)(2) of Virginia Beach asked speakers to avoid attacks or accusations regarding the honesty, character or integrity of an identified individual or group.

Frank LoMonte, the executive director with the Student Press Law Center, said policies like this are fairly common throughout the country.

“To my knowledge no one has ever brought a constitutional challenge because the only ‘penalty’ for violating the ‘rule’ is that your speaking time gets cut short, but I cannot imagine how this rule could possibly hold up to a First Amendment challenge,” he said.

The school board can limit time, manner or method, such as asking you to keep your voice down or to not go over the allotted time. The board does have a limited ability to enforce limitations on a message.

“You couldn’t demand to have three minutes at the podium to give a campaign speech for Hillary Clinton,” LoMonte said. “But as long as you are addressing a subject within the school board’s jurisdiction, then they have almost no legal authority to restrict the content of your message.”

These rules are often justified by boards as an attempt to prevent people from going into personal attacks on teachers or administrators, and also to keep meetings in line. But LoMonte said there are less drastic alternatives.

“If a person launches off into a defamatory rant, then the school board can pull the plug, but that doesn’t require completely banning references to school personnel,” he said. “For example, this rule would equally ban me from saying, ‘Happy birthday, Principal Smith,’ which is entirely harmless.”

However, stakeholders have the right to be critical in a limited public forum.

“If I am a citizen who has a problem with the way a principal does her job, I have a right to use that comment period to register my opinion about the performance of a powerful government official,” LoMonte said. “If the school board cut me off solely for mentioning a name or a job title, I’d have an excellent First Amendment case.”

City Attorney Taylor Williams, who met with Clark and this reporter not long after the publisher wrote a column challenging the rules, used Steinburg v. Chesterfield County Planning Commission to defend the policy.

In this case, Steinburg’s claims were dismissed. He had filed his suit stating his First Amendment rights were violated when the chair had him removed from the room. Steinburg also said he was unconstitutionally silenced while speaking because the commissioners disagreed with the viewpoint he expressed that criticized the way in which the commission was conducting its business. He cited Bach, but the U.S. District Court in Richmond found that the Bach ruling was inconsistent with the specifics of this case.

The court claimed that a content-neutral policy against personal attacks is not unconstitutional on its surface, as long as it is serving the purpose of keeping decorum and order. However, the finding did not preclude a challenge based on the misuse of the policy to chill or silence speech in a given circumstance. Further, the Chesterfield-based commission later dropped the “personal attacks” policy in 2006.

“In plain English, the language I have highlighted in Policy BDDH in paragraphs 5 and 8 creates a slippery slope,” Williams said of the more than 15-year-old rules. “Depending on circumstances and application, the words could be a violation of free speech under the First Amendment (Bach) or could be the hook to return to the topic of discussion, to restore order and to prevent the meeting from spiraling out of control (Steinburg).”

At the March meeting of the school board, the policy discussions were tabled so that Williams could further research it.

“I am looking into finding some additional language or creating new language that might be less offensive to free speech to go in paragraphs five and eight,” he said. “Something that might allow some criticism, as long as it is not a personal attack kind of criticism.”

School board member and vice chair Will Councill said this item will be up for more discussion in a future meeting.

“I see both sides of it,” Councill said of the issues of balancing the First Amendment and keeping order. “We’re just going to go back and talk and see what we can come up with, and get it right.”

However, he would not say which way he was leaning.

Chair Edna King and several other board members could not be reached for comment.

The school board’s next regularly scheduled meeting is set for Thursday, April 16, starting at 7 p.m.

Zurfluh hopes they change the policy to allow for more reasonable discourse, as do other members of the community, including Howie Soucek, whose wife was a long-time English teacher in the division.

“I was concerned and offended at the actions of the school board in shutting down people who are trying to speak,” he said of the recent meetings involving the gifted program. “I thought that was inappropriate. I know there are a lot of people that were really offended.”