Dred Scott descendants call for reconciliation

Published 6:30 pm Friday, April 5, 2019

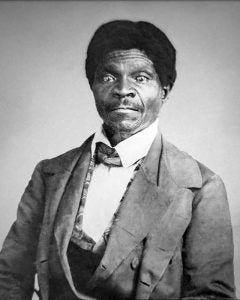

- Lynne Scott Jackson, great-great-granddaughter of Dred Scott, and Charles Taney, great-great-grandnephew of Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney, shared their story of repentance and healing with students, professors and the public at Virginia Union University. Courtesy | VCU Capital News Service

By Adrian Teran-Tapia

Capital News Service

[Editor’s note: Dred Scott was born a slave in Southampton County in the early 1800s. There a highway marker at the corner of U.S. Highway 58 and Buckhorn Quarter Road to commemorate his life.]

RICHMOND

Descendants of the central figures in the infamous Dred Scott case said Confederate monuments should be moved to museums where people can learn about America’s troubled history of race relations.

That solution was endorsed by Lynne Scott Jackson, great-great-granddaughter of Dred Scott, and Charles Taney, great-great-grandnephew of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney. Justice Taney wrote the 1857 decision that blacks could not be citizens — a ruling that set the stage for the Civil War.

Jackson and Charles Taney shared their stories of repentance and healing with students, professors and the public Wednesday at the Claude G. Perkins Living and Learning Center at Virginia Union University. The discussion was hosted and organized by Virginians for Reconciliation in partnership with VUU and Virginia Commonwealth University.

Among other topics, Jackson and Taney discussed what to do about statues erected decades ago to honor Confederate figures like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. Those monuments have been a hot topic in Virginia and other Southern states.

Jackson said that rather than removing or destroying of the statues, there is an opportunity to learn.

“I say we should move, not remove,” Jackson said. “These statues play a role in our country’s history that we should not ignore.”

Jackson, the founder of the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation, said she was approached by Charles Taney’s daughter, Kate Billingsley, in 2016 about attending her one-act play “A Man of His Time.” That was the first time she met a Taney descendant in person.

The play centered around a fictional meeting between a Scott and Taney descendant. In the play, the fictional apology in the play did not go well; however, in real life backstage, Charles Taney offered an apology that he said was long overdue not only to the Scott family but to the African American community.

Taney said the first step in the healing process is recognition.

“The person who has offended has to recognize that, and they have to go to the person or people offended and say, ‘We recognize that we hurt you, we regret that and we ask for forgiveness,’” Taney said.

Taney said he apologized not only for the court decision by his ancestor but for the ruling’s specific words that he said were “deeply hurtful to an entire race of people.” (Among other things, the ruling said black people were “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”)

“The words are hard to hear,” Taney said, “but you have to listen to them to face the truth.”

Jackson said that she appreciated Taney’s honesty and that his words made it easier for her to accept his apology.

Taney and Jackson said the focus of these discussions is not to gloss over what happened but to accept the past and take something positive from it.

The speakers also addressed Virginia’s history with slavery. Jamestown was the first place enslaved Africans were brought in North America in 1619. Jackson said this discussion is a chance for the state to turn controversy to opportunity.

“I would love to see the reconciliation model we offered to become so effective that [this state] could come full circle — so at the end of the day, you’re going to undo that history, and it can be Virginia that has the reputation for reconciliation and not just the 400 years that we already know,” Jackson said.

Taney added, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if a state south of the Mason-Dixon Line showed the way? That could be a very powerful beginning.”

Former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell attended Wednesday’s event and applauded Jackson and Taney for sharing their personal story of forgiveness and acceptance.

“Hearing this message is a great opportunity to say what’s in our hearts, what are our prejudices, what are our biases that prevent us from loving our neighbor,” McDonnell said.

“I am just so inspired by this time that I spent with these two beautiful human beings that have found a way across the divide of history to set a model for how to reconcile. That’s what we are going to work on, and there’s no reason Virginia can’t take a historic role doing this as a model for the nation.”