Franklin’s liquor history

Published 6:02 pm Monday, November 1, 2021

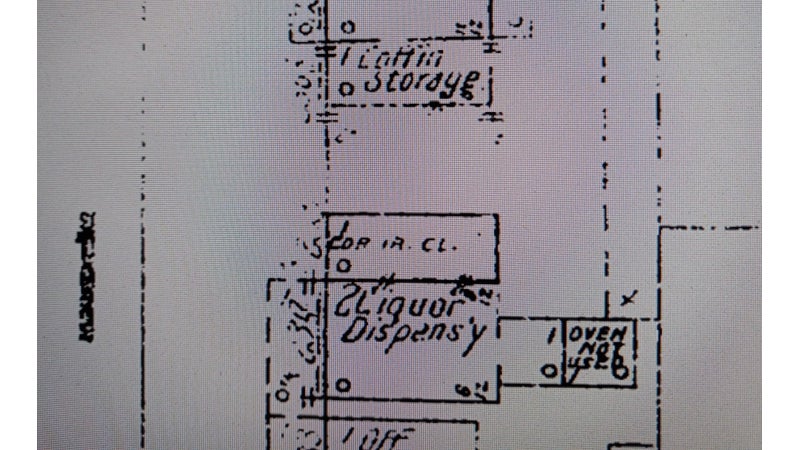

- Above is a copy of the 1902 Sanborn Town plat showing the location of the Franklin Dispensary on 1st Avenue. (Photo submitted by Clyde Parker)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Clyde Parker

Up to about 1891, Franklin was a typical “wet” town. Going back in time to the mid-1830s, when Franklin was first established as a village, liquor manufacture, distribution, and consumption was not controlled. However, starting in the latter part of the 1800s, it was controlled to some extent through a county licensing of establishments. In 1891, though, the citizens of Franklin, led by the WCTU and the churches, petitioned Judge Barrett of the Southampton County Court to refuse liquor licenses for Franklin, which petition was granted. As a “no-liquor” town, Franklin was a failure and it returned to its previous ways — blatant production, distribution, and consumption. Liquor was being brought in weekly by the buckboard-load and every known “wet person” knew where in town he could get all the liquor he wanted. It was common report that all one had to do was to go to some vacant lot and shake a bush, and a coffee pot or tin bucket would be found containing his favorite kind.

In 1892, after the no-license system had been in effect a year, a local option election was held — whether to re-establish licensing of alcohol. The “wets” won by one vote. A prominent worker for the “dry” cause was Rev. C.C. Werenbaker, pastor of the Methodist Church; but he, having failed to register, could not vote. Had he been in a position to vote, there would have been a tie; and it was generally thought that Judge Barrett would have decided in favor of the “dry” element. Illogically, though, had the “drys” won, alcohol production and use, would have still existed — but illegally!

So, local licensing of establishments to legally dispense alcohol was reinstituted and this system was in place right on up to the early 1900s. Around that time, the Commonwealth of Virginia, following the lead of other states, especially South Carolina, decided to consider state-controlled liquor stores. So, for the first time the Commonwealth of Virginia got involved with the liquor business.

And, for whatever reason, Franklin was chosen as the first Virginia location, in 1902, of what was called a dispensary. It was located in a building on First Avenue, right next to the alley that ran behind the stores that faced Main Street. Later, the dispensary building was used for other purposes — including William Branch’s first shoe store.

The Franklin Dispensary was managed by three commissioners, some of Franklin’s most prominent and best citizens: Cecil C. Vaughan Sr., R.S. Fagan and John C. Parker. Mr. Fagan was designated as the purchasing agent for the dispensary. The profits from liquor sales were divided as follows: three-eighths to the Town of Franklin, three-eighths to the district, and two-eighths to the state. From the profits received by the town were built concrete sidewalks on Main, High and Clay streets and First, Second and Fourth avenues. Some of the residents were at first loath to use the sidewalks, claiming they had been built with “blood money.” And, the fine and grand Franklin Elementary School, built in 1905 and located at 516 W. Second Ave., was made possible through funds derived from the dispensary. Many people were especially upset by the fact that the education of the town’s children was being accomplished through the sale of evil spirits. All along, the Southampton County Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was vehemently opposed to and disdained alcohol in general; and, in particular, the presence of the liquor dispensary in the community. The public outcry against any official town connection with alcohol became so great that, in 1907, the Franklin Dispensary authorization was abolished before all the bonds issued for these improvements could be paid. Franklin was the first town in the state to have a state-controlled liquor store and was the first town to abolish it. After the abolishment, there was very little control of alcohol, at any level, for many years.

All the foregoing, of course, was much before the national institution of prohibition.

In January 1920, led by Dr. Rufus L. Raiford, of Sedley, Southampton County, joined in on the nation-wide effort to prohibit alcohol production and distribution. A national organization, called the “Anti-Saloon League of America,” was leading the movement; and, that organization combined with the efforts of the WCTU and other anti-alcohol organizations — including churches — eventually led to the establishment of prohibition in 1920.

Prohibition was described as the legal prevention of the manufacture, sale, distribution, and/or transportation of alcoholic beverages in the United States. Prohibition, however, did not specifically outlaw alcohol consumption. In December of 1917, both chambers of the United States Congress passed legislation that would bring about prohibition; and, in January of 1919, in order to make it in accordance with the United States Constitution and official, ratification of that legislation by the requisite three-quarters of the States of the Union was completed. Thus, the 18th Amendment of the United States Constitution came into being and it was to be effective Jan. 17, 1920.

However, actual enforcement of the legislation was slow in coming about. In some cases, for an extended period of time, enforcement was non-existent in some areas of the country.

Although prohibition was established and was supported by many people, in actuality, millions of Americans were still drinking alcoholic beverages. Because the law did not specifically outlaw consumption, many people stockpiled alcohol and figured out ways to obtain it. This gave rise to bootlegging (illegal production, sale, and distribution) and “speakeasies” (illegal and secret drinking establishments) which were capitalized upon by organized crime. Gangsterism and turf battles between criminal gangs were prevalent.

Locally, here in Southampton County, there were still some establishments that were classified as saloons. In Franklin, alone, there were several such establishments — especially, up and down Main Street, on First Avenue, and along Railroad Avenue. And, a good number of illegal production facilities (sometimes called “liquor stills”) were in operation, especially in rural areas.

So, even though legal prohibition, in accordance with the 18th amendment, extended from 1920 to 1933, official and legal enforcement of it was very difficult. In support of federal, state, and local law enforcement, to help counter the many and varied violations of the law, organizations such as the Anti-Saloon League sprang up throughout the country. Of course, the WCTU had been in existence for decades; and, a great number of churches had long been in opposition to alcohol in all its forms.

In the long run, it became obvious that prohibition had caused far more problems than it had solved. Of much concern was the increase in criminal activity, public corruption, and, in general, a prevalent casual disregard of law. An organization called “Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform” was at the forefront of the movement to repeal the prohibition law.

In 1933, the 21st amendment (to repeal prohibition) of the United States Constitution was ratified which automatically and officially repealed the 18th amendment of the United States Constitution (the establishment of prohibition).

On Aug. 27, 1933, Virginia Gov. John Pollard called the General Assembly into special session — to legalize 3.2% alcoholic beverages.

On March 22, 1934, the Virginia General Assembly voted to adopt a liquor control plan — and created the Virginia Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control.

However, the creation of the Virginia ABC system did not, obviously, preclude the continued manufacture, distribution and consumption of illegal alcohol. For a long period of time, “bootlegging,” liquor stills, and “nip” joints continued in existence in some parts of our area.

And, even though the Virginia ABC system was establishing stores in communities across the state, Franklin did not have an ABC store until 1950; before that, people from this area had to go to Suffolk to purchase legal liquor.

CLYDE PARKER is a retired human resources manager for the former Franklin Equipment Co. and a member of the Southampton Historical Society. His email address is magnolia101@charter.net.